Seeds of...

“Ini biji,” I say, “Here is a seed,”

I am in Bandung at our organization’s annual work-planning meeting. I am giving a talk on a new strategy to decrease deaths in our hospitals. EMAS currently supports twenty-three hospitals, but this number will grow to over fifty this year and over one-hundred-and-fifty the next. Even in front of my peers, I wonder if this “fuzzy” math or a chance to seriously change Indonesia’s health landscape.

“Biji perlu apa tumbuh,” I say, “What do seeds need to grow?”

The EMAS leaders in the audience lean in. I have on the screen a single round green projection, the biji. What they will later see is the seed (the facilities we support) sprout with the nourishment of dirt (community involvement, local buy-in, budget) with the eventual development of leaves (quality services) and finally flowers (ability to teach and spread), leading to a pretty garden of plants (health care system) that any worker or citizen could feel proud to work on.

It took me at five hours to animate this simple appearing seed. Call me old, but damn it if power point does not have a cartooning function. Damn me too if Mac Computers are truly 100% compatible with Microsoft PC’s. Upon completion of my health care garden on transfer, all my leaves and stems turned orange. Damn me three if I should spend ten hours preparing for a forty-minute talk. But this my chance to make a fundamental change in how EMAS works. Sometimes I rationalize that important things take time.

“Tahah…Air…Pupuk…Jaga!” shout the audience, “Soil…Water…Fertilizer…Care!”

“Yes, so it’s not just about the seed,” I match, “Jadi, bukan hanya biji. Hal penting termasuk kondisi, lindungan, konteksnya juga…It’s also about getting the conditions right for growth. There is patience and urgency in all of this. The growing season is now. But before a seed grows up, it must grow down.”

The decision whether to try to give this talk in Bahasa Indonesia was a difficult one. As a program Director and I want to forestall the impression that I am idiot. I have to balance my communication goals in the present with the need to improve my communication skills for the long term. My colleagues are 98% Indonesian. Did I really expect them to listen to a treatise on clinical decision support in English? How f*$ked up is that? (I am not talking about the subject matter.) Can an Indonesian travel to the U.S. speaking in his native tongue and expect to be heard? My approach this morning: Speak as much Indonesian as I can.

In the beginning, I think that I have the audience in the state I want them. They are all at once amused, active and attentive. I have worked hard on my analogy—the biji. While EMAS has focused on health care improvement through a hospital’s ability to govern, I am also suggesting a focus on the outputs of governance. What exactly do we want hospitals services to do with newborn babies who struggle to breathe or birthing women who experienced prolonged bleeding? How long do we wait for quality services to develop? What tools can we give the system to make sure it governs well?

Stakes of hospital organization game

It is later in the afternoon that I discover biji is Indonesian slang for testicle. If you want to get away from the pun, you use the word “benih”. Since I had never heard of “benih” before, I apparently said “sprouting testicle” in my talk over and over again.

It was a humble, conservatively dressed woman named Ita, who works in our Jakarta office, who educated me on my mistake. Ita is married to a Dutch man and speaks impeccable English. Her hair covered in a pink wrap or Hijab, as is the custom of Muslim women, she gestured to during the afternoon break to an area away from the tea and cookies.

“Uh, excuse me Pak Wilson,” she whispered, “I have something to share with you that I think you will know. I kind of feel a little uncomfortable speaking to you about this”

“What is it Ita,” I answered, “it’s not a problem. You can tell me anything.”

“Well you know the talk you gave this morning,” she said, “It was very good.”

“Thank you, Ita,” I said

“But when you used the word Biji,” she said, “well, in Indonesian this term has additional meaning.”

“Oh,” I said, my voice falling, “what meaning would that be?”

“Well in Indonesian,” and at this point Ita leans into me and I into her. She drops her voice volume futher, looks both ways and then back to me, “well in Indonesian…the word biji…for men…can also means BALLS!”

Ita says BALLS with almost a shout and I don’t know if I am more startled by this, a humble Muslim woman’s knowledge of English slang, or the implications of comparing EMAS, our work, and Indonesia’s health care potential to scrotal contents.

So the conversation I thought I was speaking:

“This is a seed.”

“You can think of what we are doing as a developing seed”

“As planners, we have to think about what we want our seeds to eventually look like.”

“We have to grow our seeds in the context of the fruits we want to see.”

Really went as:

“This is a (green) testicle.”

“You can think of what we are doing as a developing testicle.”

“As planners, we have to think about what we want our testicles to eventually look like.”

“We have to grow our testicles in the context of the fruits we want to see.”

Serang baby #1 waiting...

Of course, I got into this mess months before in Serang. In the emergency room I met two babies of about equal weight--1.2 kilograms or 2.5 pounds-- the weight of a loaf of multi-grain bread. I was there on a field visit and I asked the sweaty overwhelmed emergency doctor the plans for the two babies. One had been referred from a neighborhood health center and the other brought in by the parents because of yellowing skin. The emergency doctor explained, while rustling unsuccessfully through stacks of folded grey papers on a stained clipboard that he had called the pediatrician in the neonatal unit but she had told him that the ward was full. He then attempted to arrange a transfer to another hospital but the parents, probably suspecting correctly that their care would not be better elsewhere, refused.

So the babies were kind of stuck, geographically and medically. They weren’t located in a place in the hospital with the experience to care for them and they weren’t getting the treatment they needed with few to intervene. The parents weren’t even allowed in the room. One baby was on an open warmer, its near translucent fragile skin exposed. Another was in an incubator hidden somewhere beneath layers of patterned cloth. You really had to work to find the baby. One baby was getting only one of the two recommended antibiotics for very low birth weight babies. The other was getting the right pair of antibiotics but one at the wrong dose. The first baby was receiving oxygen but didn’t need it. The second was attached to an IV bag, which had stopped dripping long ago.

Both these babies would die because of finite misallocated resources. I felt paradoxical helplessness and optimism. I couldn’t do anything for these babies in present besides trying to cajole the neonatal ward to accept the baby (they refused) or rolling up my sleeves to care for the babies myself (an activity not planned for this trip which would impede the trip’s longer term purpose) but I could see how new EMAS clinical support systems implemented well could save patients like these over and over again.

“Well it looks like you are a little overwhelmed,” I said to the doctor, “you should not be put in such a position.” Nampak, anda perlu lebih banyak bantuan. Anda tidak seharusnya ditempatkan di posisi ini.

To this the doctor looked to the ground.

It is in the middle of the morning’s talk that I ask my audience what to do to support the untrained Serang emergency doctor. They suggest things like teaching, training, continuous education and staffing…the usual bullshit.

“How about this,” I say, “Anda semua pernah denger ‘check-list’ ”?

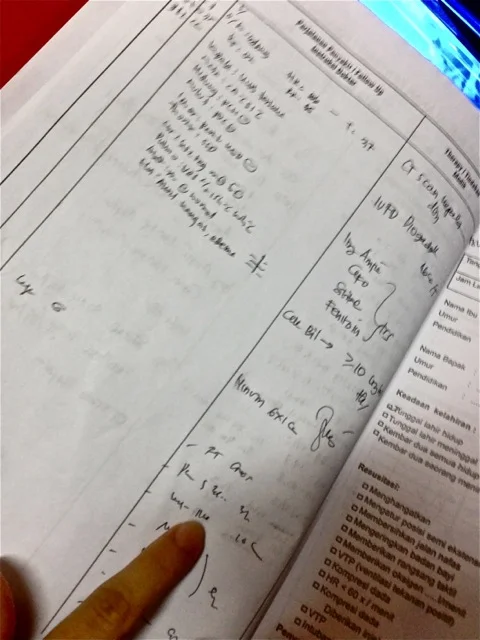

The current medical record - a blank canvas for artists to fill.

I show my colleagues how we need to take the brains out of medicine when there is no need for brains. I show them examples of checklists with orders for premature babies already written out. A baby comes to the emergency room weighing 2 pounds and they will automatically get 50 milligrams per kilogram of Ampicillin twice a day and five milligrams of gentamicin per kilogram every other day. Similarly, since they will not be drinking, the type and volume of IV fluids are already worked out by weight and age. There may not be a machine to drip the IV fluids, but there can be a twenty five cent fluid reservoir which contains the maximum amount of fluids to be dispensed in a nursing shift, avoiding the risk of drowning the babies heart and lungs with uncontrolled flow.

“Why do we ask our doctors to guess the treatment for well known diseases and conditions? “I ask, “what are the consequences of a health care system that does not follow the evidence-base?” Apakah seharusnya mengijinkan doctor-doktor mengira memperlakukan? Hasil sistem ini apa?

When I show a picture of a crashed plane from the 1977 Tenerife disaster, the largest in aviation history, I know that my colleagues kind of get it. The problem at Tenerife was that in the 70’s, like the medical system in 2013, there were relatively few structured processes of the trade, including at takeoff. In a fog storm, an impatient KLM pilot told air traffic control that he was ready to go. Air traffic control replied, “Yes, we know you are at the takeoff point (please stand by). The KLM pilot on hearing “yes” began accelerating. His copilot questioned whether the runway was all clear, but ultimately felt uncomfortable questioning his senior pilot. He said only, "Is he not clear, that Pan American?"

Tenerife crash - March 27, 1977