Breathing In and Out

Good things are happening at RSUD Bulukumba

Every once in a while, in the hot sweaty mess, which is international health, one experiences the possibility of doing good. You may be in a hospital, a meeting, a field, at a roadside shop, or tiny school. You may be teaching, digging, treating, eating, even embracing. The realization settles on you like a puff of angel’s dust—entirely unexpected but with understanding that with hard work derives purpose and nothing happens alone.

On this day, our team is in a hospital called RSUD Serang, a dusty facility two hour’s drive away from Jakarta. Serang is a prototypical Indonesian public hospital, comprised of random one and two-story buildings interconnected by outdoor tin-roofed walk-ways bordered by deep cement gutters. The floor is white slick marble painstakingly mopped. Wild grass, potted plants and an occasional local statue fill intervening areas. The feel of the area is not unlike a well-frequented community garden. Families abound, some moving in zigzag on self-guided tours. Others sit on bamboo mats reading the newspaper and eating out of a large centrally located aluminum pot. Children run and hide betwixt the walkway pillars or try unsuccessfully to sneak up on twitchy geckos. A collision of shoes, sandals, and flip-flops lie scattered at building entranceways where activities have moved from outside to in.

Keep on the grass. Deli Serdang Hospital in Medan

The external appearance of hospitals like Serang does not necessarily imply the quality of care practiced in them. Serang has a new emergency room painted an optimistic pink. Its wards and common areas are squeaky clean. The nurse and midwives approach their duties with astounding spunk. But it is also a place where patients go to die. When I first drove up to Serang’s entranceway eighteen months ago, I asked my taxi driver about the reputation of the facility as I typically do when I want to get the true story of a place. He said “lumayan” or “average”. When I asked him if one would choose instead the private hospital that we just passed, he said “pasti” or “of course” as if I had asked him if Indonesians enjoy Durian.

In the intervening period I learned that medical specialists do not to spend more than 2-3 hours a day at Serang because of a miniscule $200 a month public salary, instead opting to work at private health facilities, where they earn ten to twenty times more. Within the hierarchy of Indonesian culture this personal choice spells medical disaster as those who remain in the hospital do not have the skill or authority to deal with emergencies that inevitably arise. On the flip side, patients who aren’t currently experiencing emergencies, receive care plans inconsistent with the complexity of their illness, setting them up for future emergencies. While it is true that specialists are usually available 24/7 by phone, along the logical cadence of grave illness, this provides little consolation to patients requiring the outcomes of time, sight and touch. Simply put, the math doesn’t work. In a six-month audit of pediatric deaths across twelve hospitals in Indonesia’s largest provinces, we found that in over 90% of cases, patients died in the absence of a doctor-- at night, over the weekend, during prayer time. We found that over 80% of patients were subject to dangerous medical practice like getting bicarbonate for severe dehydration as opposed to rehydration or intubation despite normal documented respiratory rate. In 50% of the cases, we could not determine the exact cause of death because the medical notes were incomplete or illegible. At RSUD Serang, the formal cause of death listed for all maternal and neonatal deaths is simply “sakit” or “sick”.

Families waiting for news of their loved ones on the floor

I have learned that in promoting change, one best work with partners or organizations on the brink of success versus those, which have consistently shown themselves to not be serious. Change is complex and to a threshold degree, institutions comprised of people must be primed to want to learn and act within the finite time and monies of international health endeavors. So when deciding months back to which health facilities EMAS should give its new CPAP breathing machines, RSUD Serang was the furthest place from my mind.

“How about RSUD Serang?” recommended Lilik, “they are close to Jakarta and you can monitor the intervention there.”

“How about that garbage can,” I said, “Saya tidak mau buang mesin.”

“Saya piker Anda punya sikap yang kurang,” Lilik said, “you need to change your attitude.”

“I know,” I said, “Tuju.”

“We can do it,” said Isti Serang’s program manager. Isti is a perpertual optimistic, “jangan lupa kami!”

Between Dr. Lilik and Isti, who used to play semi-professional basketball, I am helpless. I know they are Indonesian, excellent and more measured than I. It is important that they not I decide these things.

“Baik,” I say.

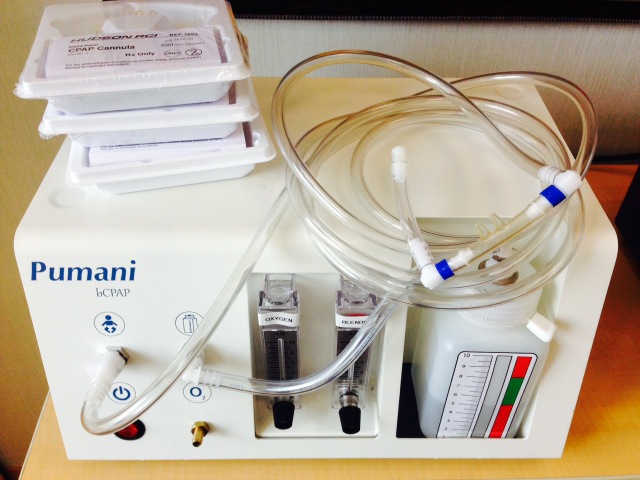

Simple "bubble" CPAP but a life-saver

CPAP stands for continuous positive airway pressure. In adults and children, but especially babies, premature or diseased lungs are sticky, collapsing easily when breathing-out making them subsequently difficult to re-inflate on the breath in. CPAP gives the diseased lungs a set amount of pressure so as to keep them always partially inflated so they never have a chance to collapse. CPAP also gives this pressure from the nose through snug fitting nasal prongs, avoiding the complication associated with tubes placed directly in the larynx (intubation), including infections, pressure sores, and suffocation when the power goes out. CPAP has shown to decrease death of premature babies by up to 50%. This includes the very low infant baby who has yet to experience respiratory distress but will eventually experience this, statistically.

EMAS is not a procurement organization and never thought to provide partners equipment, which tends to be too expensive anyway. But in working with partners over the past year, I found that many of our hospitals did not have access to certain life saving technology without which it didn’t make a difference how prepared, organized or skilled we tried to make them. This technology included CPAP but also IV- pumps, ambu-bags with proper sized masks, pulse-oximeters and deep line sets. I also noticed that most partners really wouldn’t work with EMAS well if we didn’t start first with their priorities, which often included access to these selfsame life-saving technologies. No health professional likes to watch a patient die and not be able to do something. We concluded that for certain partners, we would present limited technology in the context of organization and skill building. For example, we could gift a hospital a CPAP, so long as they trained on the machine, showed and documented its proper use and reported on their successes and challenges, the fundamental purpose of EMAS interventions, really.

What happens when you give people what they want

How we got our CPAP machines was really quite miraculous. In Jakarta, I recalled an organization many years prior called Third Stone Design based in San Raphael, California north of San Francisco. One of third Stone's partners had tried to get me to try their $400 CPAP machine when I was living and working in Liberia, 2011-12. While CPAP machines usually cost $10,000, in Liberia the skill level was so low, it didn’t matter what the cost differential. There, we were trying to get nurses to accurately measure vital signs, doctors to come to work at definite times, our pharmacy secure and stocked. Giving CPAP to our facilities would have been like giving lobster to a baby for an evening meal. In contrast, Indonesia is the 17th largest economy in the world with relatively well-trained nurses, midwives and general doctors. The country has 17,000 islands and 250 million people so resources are scarce too depending on where you are. To make a long story short, I visited Third Stone on one of my visits back to the States and they graciously gifted us two CPAP machines with promises of more to come. I didn’t even have to ask. I personally hand carried the machines, which are elegant and robust, back to Indonesia in a sturdy Styrofoam-lined suitcase. They landed in Jakarta with a clunk off the airport conveyer belt.

Impact from half a world a way - Third Stone Design

The hospital leadership, nurses and pediatricians are crowded into the Serang’s meeting room. There are at least 40 in the audience, which would not be atypical as Indonesians like formality, events and the sticky-sweet box snacks that accompany them. My boss had tried to cancel the event, citing worry about EMAS liability. I cited that the machine had been tested in Malawi for years with amazing results. Also, Serang hadn’t had a working CPAP for over two years. Wouldn’t something be better than nothing?

In the end it wasn’t my persuasive abilities that convinced my boss to allow the event to proceed, but the pressure from the partner who wanted the machine. The party had already been organized. The three pediatricians invited. The Vice Director would by MC’ing the festivities. Our EMAS Serang provincial leader, would absolutely not accept a cancellation, writing long convincing emails to my boss, which made me smug.

I sometimes do better when presenting in Indonesian. There is no way I can over prepare-- my tendency--because so much attention needs to be paid to the finite words I know as opposed to any unachievable poetic flourish. This actually makes me more communicative, because I speak according to feel. I converse with audience as opposed to speaking to them.

“Thank you so much for coming,” I say, “Saya mau berterima kasih kepada rekan rekan, membiarkan saya kesempatan untuk memperkenalkan mesin CPAP.”

“RSUD hasn’t had a CPAP in two years! Dua tahun! But you are about to have one today.”

“CPAP can save premature babies 50% of the time. Right now you can only give them oxygen by nasal cannula or mask and it isn’t enough and we know it.”

The nurses who woman the neonatal unit nod.

“I know you say you have CPAP. In fact you say you have two CPAP but in America you only have CPAP if it is working and your two CPAP machines are broken. So please don’t confuse this simple American by saying you already have CPAP because you don’t.”

Typical Indonesian broken CPAP

The audience laughs. I have known most in the room for a long while and they know I don’t mean harm but am serious too. Dr. Silvi, who has been patient, raises her hand. Is the CPAP good?”

“Yes Dr. Silvia,” I repy, “saya udah menunjukan bukti sobre mesinya. I have already shown you the literature on this CPAP. It has been tested in one of the most difficult parts of the world with amazing success. Here I think it will even do better.”

“But it’s so small,” continues Dr. Enzi, “begitu kecil.”

“It looks simple because it is. Unlike the CPAP machines that you say you have, it doesn’t have a humidifier, which I know will concern some of you. But the last time I checked Indonesia is pretty humid and the machine draws air from around it. Look at me sweating! Tell me that it is not plenty humid here.”

My Indonesian colleagues chuckle to confirm.

"But true, the studies have not compared this CPAP machine to a machine with a humidifier which I admit is the standard of care. But right now you don’t have anything and compared to that, this CPAP works just fine. Without a humidifier ironically, this machine might save more lives because it is the humidifier, which often breaks and costs $2000 dollars. That’s five of these machines!”

“Can we have more than one,” asks the vice director.

“Woe, Bessie,” I say, “let’s start with one. Before you wanted none! Belum! Mencoba dengan ini pertama.”

The audience is leaning in. Many nurses bring hands up to the face so as to cover their teeth. “But you are convincing us,“ replies the doctor.

“That’s a first,” I say.

I start showing them the machine. It’s simple. I turn on the machine. It purrs. I show them the two sets of tubing, to what they connect, the option to pipe oxygen into the machine and the importance of selecting appropriately sized nasal prongs. I show them how to connect the prongs to the hat that attaches to my sample rubber baby with two safety pins and rubber bands.

Poor man's way of affixing CPAP tubing to hat

“Ooh,” the audience sounds. I have never felt such happiness at equivalent acts involving rubber bands and safety pins

We move into the applied portion of the presentation. I invite the non-clinicians to leave if they have other business but they don’t. Within five minutes the head pediatrician Dr. Silvi, notoriously stubborn, has taken over my role, teaching the use of CPAP and the accompanying monitoring tools.

“And look Dr. Silvi,” I say, “with the tools, you don’t have to always be there to teach. We have made these decision support tools to make sure your staff knows when to use the CPAP and how to makes sure it is working when it is attached.”

Dr. Silvi at first furrows her brows at the tools but they soon lift up. She sees how clear the tools present information that is easily forgotten such as the level of respiratory distress that rationalizes application of CPAP or what mixture of air flow and oxygen produces 40, 50 or 60% mixtures.

Dr. Silvi leading others

Everyone has a particular focus of interest. Dr. Silvi likes the decision support oxygen-mixing table and the size parameters listed on the DST matched against the nasal prongs. The nurses like the way the tubing fastens to the hat. The director likes the sound of the machine and when no one is looking puts her hand to the metal side plate and bends down to hear. I just kind of stand back and watch. I am 24 years old again. It’s my last quarter teaching junior high school. This is what learning and change ultimately feels like.

Two hours later, the neonatal intensive care unit is using CPAP for the first time in two years. I know this only when I have already departed and stuck in Jakarta traffic. Isti sends me a picture with the word “HEBAT” or “fantastic.”

The picture shows a sick but well organized baby. The prongs are attached just as they should. The baby looks comfortable like a doll not quite real. Isti sends me another picture of the maintenance tools properly filled out. This is my favorite part.

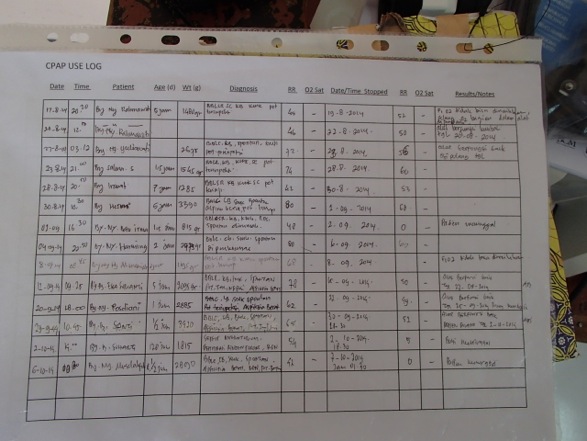

CPAP use and detail sheet. All good endeavors are managed

Later I talk with Isti, “Good thing that CPAP has fish tank pumps for engines,” I say, “they will never give out.”

“Iyahhh,” coos Isti, “you didn’t say anything about that!”

“There is a lot of things I didn’t say, “ I say, “including good work.” I can’t see Isti, but I know that she is smiling.”

“That’s good planning,” I say.

“Your welcome,” she says.

“Remember the follow-up is even more important.” I say.

“I know you always say this,” she says.

“To babies” I say, “untuk bayi!”

“To babies in Serang,” she says, “selamat bayinya di Serang!”

First baby with CPAP at RSUD Serang in over two years