Stage I

Sometimes even the remote stands a chance. Sure, the threat of diarrhea looms. Sweat has flattened the hair and shined-up the forehead. You don’t even expect your luck to last but just in case, you tap the pads of your thumbs together twenty times before anyone looks. On the car up and down from the health facility, you hold your breath for one and a half minutes. It used to be two.

It’s the second day of training in Pakpak Bharat, a district in remote Sumatera, seven hours drive from Medan, the capital. On this day, the team is at Puskesmas Sukaramai, a pretty clean, red roofed health center on a hill that literally translates into “likes being busy community health center”. Not withstanding there isn’t a single patient at Puskesmas Sukaramai when we arrive, about twenty staff are outside waiting when our SUV’s pull up. They are energetic, dressed in clean, starched coffee-brown uniforms not unlike those worn on the Star Ship enterprise. Stepping into the crowd, there is palpable excitement and I can’t help but think this could never happen back home. All around are crescendo decrescendo murmurs, the occasional squeal, the clip-clop of sandals from those running from different directions to join the circle. We greet each person with the traditional Indonesian gesture: A two handed claps of the finger tips— hold— followed by the grasping of the right hand to the heart.

This being Indonesia, we then move to photography: In front of the Puskesmas, in each examination room, in front of the ambulance and with the garden tomatoes out back. After the umpteenth photo with a startling combination of participants and individual smart phones, people laugh when I suggest in broken Indonesian that we could actually share with each other via text a single person’s shots, “Ada kemungkinan kita bisa saling bagikan foto-foto.” Then there is the singing of the Puskesmas theme song—a really a catchy tune. I am immediately reminded during the washing hands with spirit refrain about my time as a middle school teacher when I made students commit concepts on diatomaceous earth and other rocks to rap. That was less pretty.

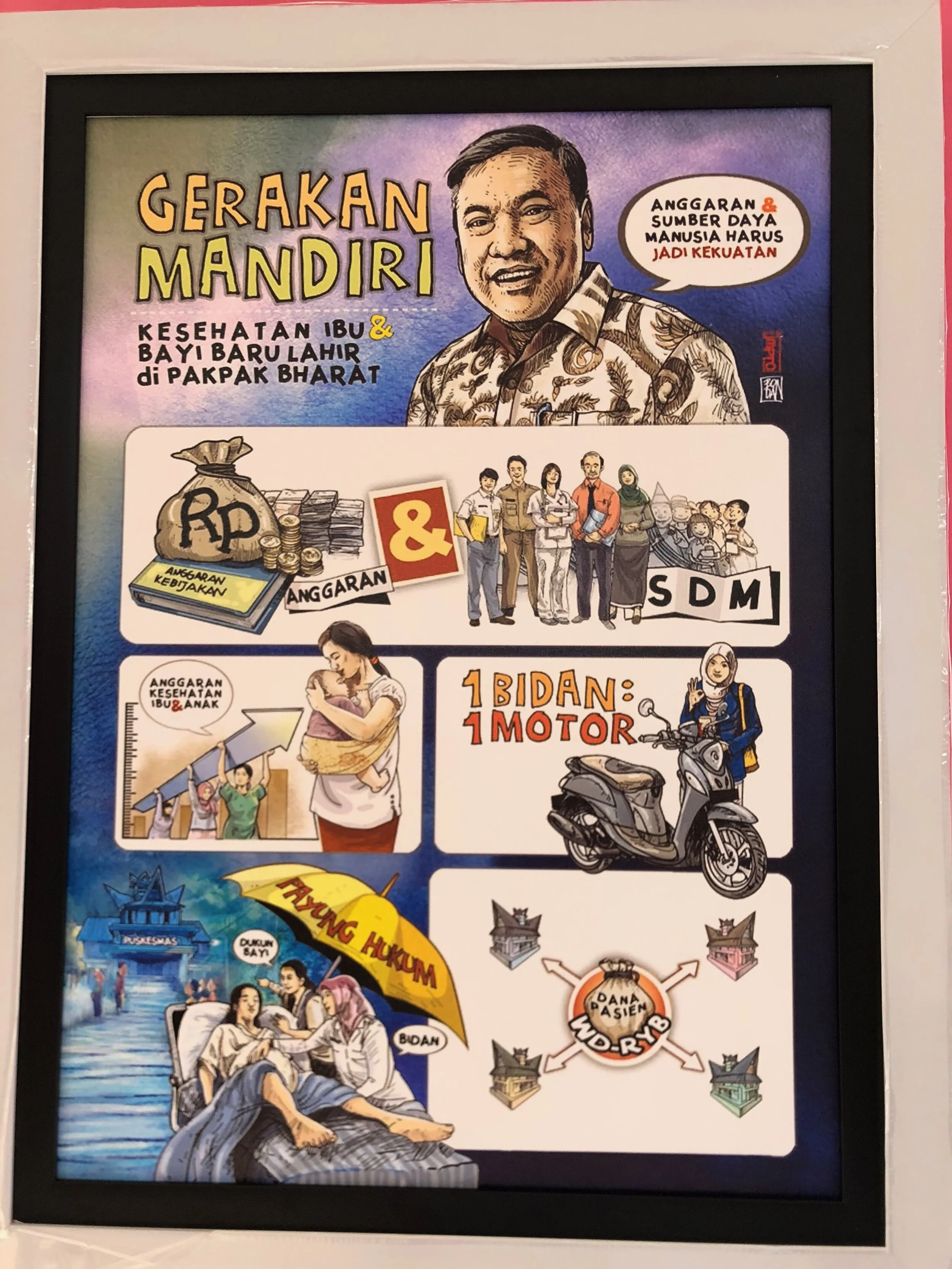

The team is at Sukaramai to implement the Walking Doctor’s (WD) electronic health system (EHS). A smaller segment of the WD team will do this again in Pakpak Bharat’s other seven Puskesmas. The system is the first of its kind in an Indonesian district with the potential to transform the way medical care is practiced in the country. Not only will it allow the organized saving and sharing of medical information across a region in heath facilities which before only used pen and paper, it will display health facility performance relative to others in near real time: How many patients were seen; what they were treated for and how; details of any patient transfer or death; whether charting is complete and diseases treated according to protocol. Since it is useless to hold health professionals responsible for that which is out of their control, the WD EHS is specifically constructed to remind doctors, nurses and midwives of vital evidence-based considerations as they work. It doesn’t matter if the condition is a wart, heart attack, appendicitis, or green vomit, one of two hundred checklists will confirm or reject the provider’s assumptions based on historical, physical, and test findings. So as to not slow down the clinician, each click of a checklist item directly populates the medical record, calls the nurse, or communicates to the laboratory—a glory to physicians who know how much time is routinely wasted writing the same thing over and over again and tracking down orders. At least this is the premise.

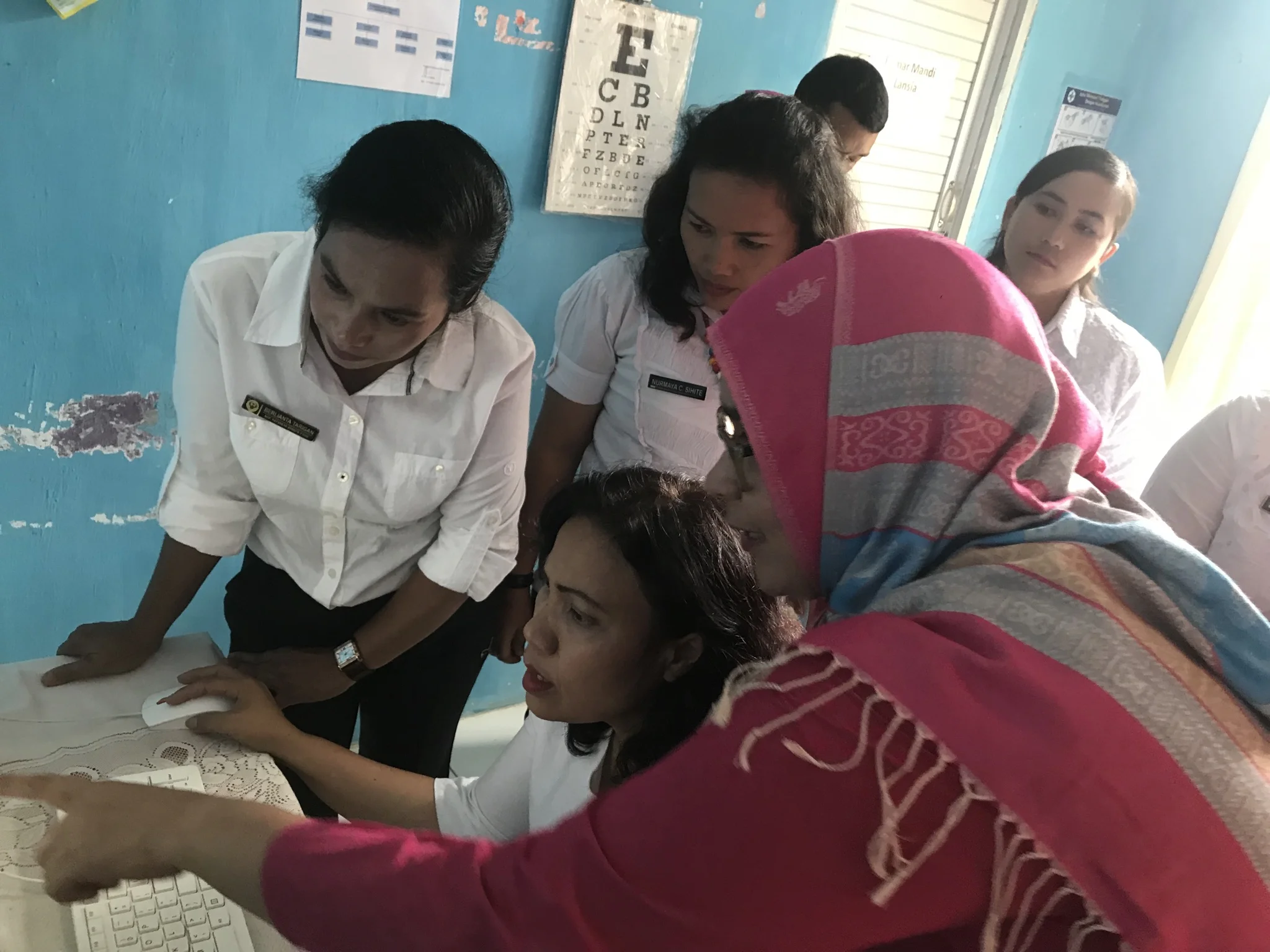

It helps that Pakpak Bharat’s Governor understands what the hell I am talking about. Fifteen minutes after a short session with him on the design and features of the system, I am surprised to find Bupati Remigo teaching staff how to run a patient through a Walking Doctor’s clinical checklist. Bupati Remigo is a vocal, charismatic, and animated man and staff and one really skinny ironic chicken naturally flock to where he sits next to one of Sukaramai’s stunningly white computers.

“This is what is means to be systematic,” the Bupati says, “Kita sebagai pertegus profesionel harus bekerja secara sistematis…You forget to ask the patient something, that’s okay. We all forget. This system reminds you: Have you had fever? Are your having trouble breathing? Has this happened to you before? As you go, you just click click click. I am not a doctor but I really enjoy this clicking.” The people around the Bupati chuckle.

Bupati Remigo stands at the four o’clock position to the terminal. Behind him are successive layers of doctors, nurses and midwives. One of Puksesmas Sukaramai’s two doctors sits to his left typing and selecting items on the screen. Periodically, Bupati leans over with his relatively giant frame to point and gesticulate as if reaching out a window to grab dried clean shirts off the line. “No, you just diagnosed the man as pregnant…yes, let’s give that sick boy a good shot…uh, I think you just killed the patient...hey, I don’t need to increase your pay. This system makes work actually fun!”

Things aren’t supposed to go this way. In Indonesia, implementing a new idea is more often than not tantamount to passion torture in the context of a really long conversation. The subtext is that you have the right to change things if you are old (check) and are part of behemoth institutions that carry the traditions of royal courts (uncheck). A medical app, forget it. The medical professional societies will kill it. Want to have a discussion on causes of maternal and neonatal death, be prepared to have three (paid) one-hour speeches by functionaries and one power point rivaling biblical text until it’s time to go home. Want to implement an electronic health system that addresses high rates of medical error in a country where doctors are prized, ha! One would have better odds of completing Jakarta’s subway-- now 15 years in the making.

I worked with the Indonesian health Ministry, pediatric and obstetric societies, local leadership and hospital specialists between 2013-15 to get clinical checklists for the country’s greatest killers approved. My teams could show that 60-80% of the time, doctors and to a lesser extent, midwives, were not following protocols proven to saves lives. I first learned this in Liberia where you would feel good about teaching staff, for example, how to manage a child with diabetic ketoacidosis with a sugar of 700 one afternoon, only to find that child dead the next morning because the insulin given was the wrong type: “They didn’t have the other kind.” You looked at the paper chart and it was empty except for the date and word “expired” hurriedly scrawled. You berated staff and they would say it won’t happen again until it did. But in Indonesia, the 17th largest economy in the world? A place where anyone with style carries a Louie Vuitton handbag?

Alas, error rates in Indonesia were just as high but for different reasons. In Liberia there are 125 practicing doctors in the whole country. In Indonesia there are twice as many doctors per capita but across 17,000 islands with most preferring only one (Java). So non-doctors in both countries, not formally trained in diagnostic care are treating the majority of patients. And even the doctor-doctors, being human and stressed from over work, make mistakes. With checklists you can kind of reverse it all, like shopping for the ingredients for vegetarian lasagna then following the recipe in your kitchen to actually make the thing—three stars if you’ve actually cooked before. Checklists in health care work just as they do in practically every other industry. It’s the best-kept secret in medicine next to doctor decision error rates.

Of course our efforts flopped over and over again. I take responsibility for attitude problems dealing with doctors I regarded as pathological but the fundamental problem was long standing ambling medical culture and inability to convince allies of the unseen. The medical societies wanted to run the checklists through committee, which was like sending medical wishes by bottle out by sea. You never heard back. Doctor groups did not practice uniformly. We could convince a majority of physicians in a facility of the advantages of organizing the medical chart around checklists, but they were too polite to force minority colleagues into compliance. This minority was too busy making money to learn and it didn’t help that working at the public hospital paid a doctor $200 a month while time at the private clinic, paid him/her ten times that. In this environment, you would watch new born babies literally turn blue in the face as midwives floundered with their resuscitation, the midwives heads tilted as the doctor in charge gave useless advice by phone from somewhere not there.

Had Indonesia changed? Had I evolved? It’s 4 pm, 7 hours later, and Sukaramia staff, Pakpak Bharat leadership and the WD team are asked to review and celebrate the day over Durian fruit in the adjacent conference room. This still being Indonesia, there are speeches before the literal breaking of Durian. But mine is actually the longest at 20 minutes due to the occasional need for translation. The speeches by others are mostly funny, thankful and extol the collaboration. The one or two times a speaker drones, the Bupati yells, “And what after all of that is your point? Do tell it but faster!”

The Bupati concludes succinctly, “I really want this. But more important, you should want this,” he pauses, “and now the durian!”