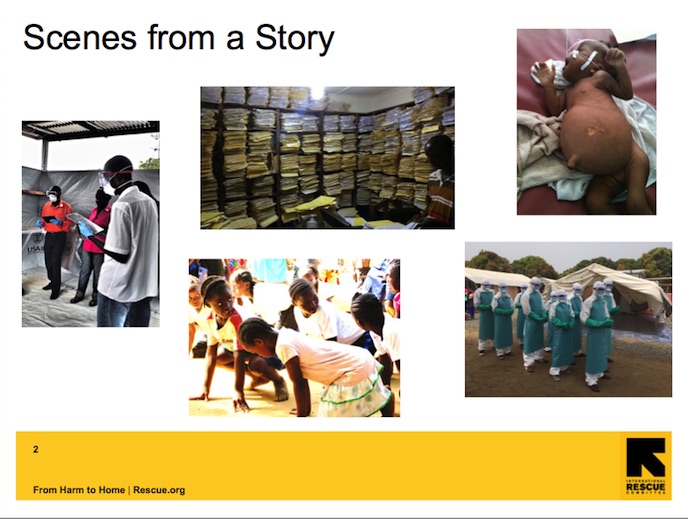

Stories need not be sensational. The story of the everyday is plenty interesting so long as we look. The story of places we have not been to, even Liberia, are not a sob story. People in other places in the world are not defined by disease, calamity and death despite the characterization. Other scenes need to be included in the story- Scenes where children play, adults work, families go on picnics, communities progress socially, economically, spiritually.

Stories on paper end. But, if you think about it, stories in the real world never end. There is always more. Each day’s end begins with the rising of the sun. Even death continues as legacy, lineage, learning, love. This means that if we want, we can insert ourselves into any story we choose. And having properly invested in the characters and context, we become part of the plot. The stories that we would want to be a part of in West Africa abound. I think there is special opportunity for season openers in EMR, rapid bed-side diagnostics, live saving sustainable technologies like infusion pumps and breathing support machines. Outside of medicine, farmers still irrigate by hand and dig with a hoe. There are few to no waste water treatment plants, garbage is strewn along the edges of rivers and beaches. Internet is spotty. It takes 4 hours to go 50 miles along gruesome muddy or rock-hard pot-hole laden roads.

I hope in this talk I have reinforced how and it is interesting and fulfilling this story-book like participation even when linked to the economies of healthcare, education, and public health. Of course participation is not enough. You make sure you’re part of a good plot-line by constantly checking your focus and by considering the multitude of views that ultimately comprise stories worth telling.

Thank you.