The (Health) Culture We Value

Children in East Harlem

Today I want to talk about the culture of health, but in the active voice: The culture we value in the U.S. health system. This phrasing assigns responsibility to the outcomes of health culture on real people. It also gives places like Metropolitan Pediatric Emergency Department in East Harlem, where I work and which is part of the largest city-run healthcare system in the country, serving 1.2 million New Yorkers, a way to address stark seemingly intractable health problems in the community that cannot be solved by current methods. We share the statistics of the rest of the country: 45% of all health care decisions do not adhere to the evidence-base. Suicide rates are at a 30-year high. 32% of our youth have been in a physical fight this school year. For minorities, things are worse. Native Americans live 20 years less than the national average of 76. Latinos are 3 times more likely to get HIV compared to their white counterparts. Homicide is the number one cause of death for black teens. Yet the country is paying 2.9 trillion dollars a year on health care costs, or 18% of GDP. This is more than twice the health care costs of most Western European countries where people live on average 4 years longer than the US population. We spend 11 times more on health care than our neighbor Cuba, which buys us one additional sick year on this world.

The culture we value. The phrase brings up many questions. First, what do we mean by culture? Are we talking about rituals, food, dress, language, music? Or are we talking about something bigger than popular characteristics of race and ethnicity. Second, who is the “we” and why does this “we” get to do the deciding? Third, implicit in the phrase the culture we value is that there is more than one culture out there. This means that there is a cultural winner and cultural losers, with most being losers. Which culture is which?

The other day, I was taking care of a transgender patient in Metropolitan’s pediatric emergency room. Towards the end of our time together, the patient said something along the lines of girlfriend, I know exactly what you are saying. I paused for a moment and said you know you just called me girlfriend. And the patient said, yeah I know I called you girl friend because throughout this whole time you have been cool, treated me like I was a normal person. To this, I said thank you. Later, I would think how generous was the patient and that I had just been privy to a rich cultural experience.

Health in the classroom

So culture is not confined to race and ethnicity at all. Culture is the customs, attitudes, values and beliefs of any group. This can be a group of elderly Cantonese who meet each morning to play cards, but it can also be the teenagers off the screen on the left, taking turns jumping a crevasse with their skateboards at the edge of the park. If you have problems remembering the formal definition of culture like I do, you can think of culture as simply how individuals in a group interact with one another and within the Venn diagram of interaction how group members care for one another. In my story there is the care of the emergency room, which sought to provide services to a pediatric patient, who just happened to be transgender. But there is also the care of the patient who sought to express gratitude about services rendered in addition to simply sharing her story-- another type of caring.

Of course there is good and bad care. Everyone who has ever been a recipient of services knows this. Quality of care though is not serendipitous. The root cause of bad care lies in power disparity between the provider of services and the recipient of services. The provider is the we in the phrase the culture we value and consists certainly of doctors and nurses but also clerks, administrators, policy-makers, insurance and drug representatives, teachers, politicians, staff at the housing authority, and the police --anyone who directly or indirectly but disproportionately influences the care quality of others. This unequal expression of power is common in the clinical setting where a patient comes to a doctor with a problem.

The high stakes of bad care

This patient was seen three times over two months in the ED with the diagnosis of a cold before the correct diagnosis of asthma was made. She then came to the emergency room three times over the following two months, before her respiratory distress was controlled. The mother was upset by the lack of effectiveness and efficiency of care but afraid to complain. We know for each visit, the doctors and nurses gathered the patient’s history, but from the results that they did not really hear her words.

Listening to what is said in the health system—the words people choose—is a good way to understand which culture is getting valued—the last part of our challenge statement. I learned this as a child growing up in Utah when I tried to deemphasize my Taiwanese heritage as a key strategy to not get picked on and to not stand out. When people asked me where I was from, I would answer, I am American. When they asked me where I was really from, I would play dumb and say Salt Lake City, Utah. When my parents spoke Taiwanese to me I would respond back only in English. At school I was the class clown intent on disrupting the day’s lesson with unsolicited jokes and quips, as no polite Asian boy would do.

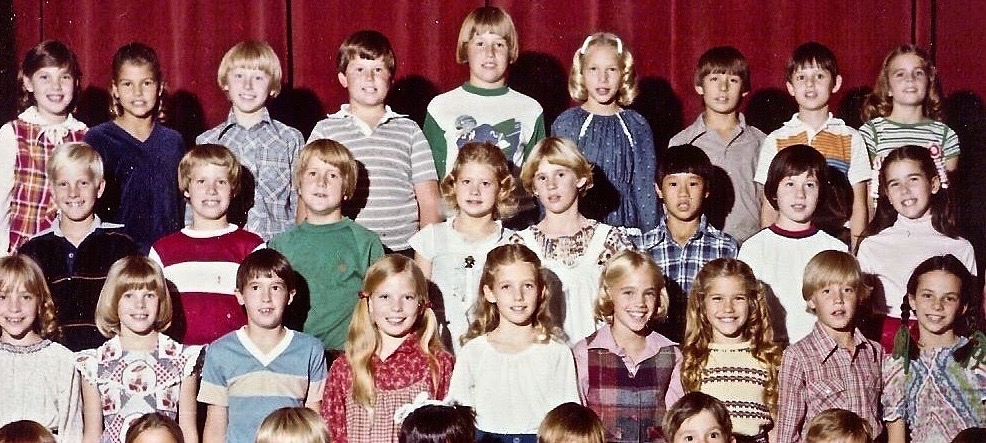

4rth grade at Ensign Elementary.

In the end, my language strategy didn’t work. Frankly, a five-foot-one Taiwanese-American speaking the language of dominant white Mormon culture is a dead end. Later, I would learn, mostly by learning to speak non-English languages, that the language you speak is the culture you value and a version of this, the need for consistency between the speaker and the words that are spoken.

So listening to the language of health providers, we often hear highly technical language. Bureaucratic language. English-only language. Time-restricted language. Language like, these people come for services and don’t even pay (when they do) or I can’t believe this woman has been in the country for 15 years and still can’t speak English (though she can), or that man’s diabetes must be out of control because he’s not taking his meds (though you don’t really know). This language reveals a care culture that has become paradoxically adversarial; at best, a type of care where individuals are regarded as the sum of their body parts. French philosopher Michel Foucault described this phenomenon in his book The Birth of the Clinic as the clinical "gaze", a separation of the individual from his/her social and environmental context to the point a whole person becomes a mere pile of cells, tissues, and organs to be dealt with. In this way, our patient with asthma reacting to the nightmarish environmental conditions of public housing can simply be provided a metered dose inhaler. Young teens who have suffered a lifetime of toxic-stress can be brought in handcuffs to the Emergency room for fighting only to be locked in an adult psychiatric unit. Associated with this clinical gaze is what philosopher John Paul Sartre calls bad faith. Adults working in the system know that the approach and subsequent treatments miss or are not quite right, but feel powerfulness or are too invested in the system to do anything about it, so they don’t.

Diversity that you feel

Things needn’t be this way. The provider culture doesn’t have to dominate on a take it or leave it basis. We don’t have to persist with purely clinical interventions that don’t work. There need not be a distorted relationship between the signifier and the signified. Imagine the opposite. A customer service mentality to care rivaling any I-phone store where the primary objective is to make sure that each client returns satisfied. Cultures working together throughout the community as if partners in a bustling full service outdoor health market. Places where people’s words are consistently nurturing as if one has been traveling for a long time and finally come home. While this alternative vision because of different demographics, locations and conditions will consist of different scenes, the common theme will be equity, the main characters everyday citizens, and the soundtrack the tenor of the words spoken. Plots will take place in a renovated Foucault-ian clinic but also outside in homes, schools, jobs, and parks-- anywhere the story of health and heath equity is accurately and logically told. Finally, the cost of this new made for reality production would be nominal. The resources we are talking about already exist. They're all human. They're in us and just need to be coaxed out. No machines necessary. The idea that you have to pay extra for what caregivers are already supposed to provide is cynical. As my father says even to me now, one only needs an attitude adjustment.

Working together